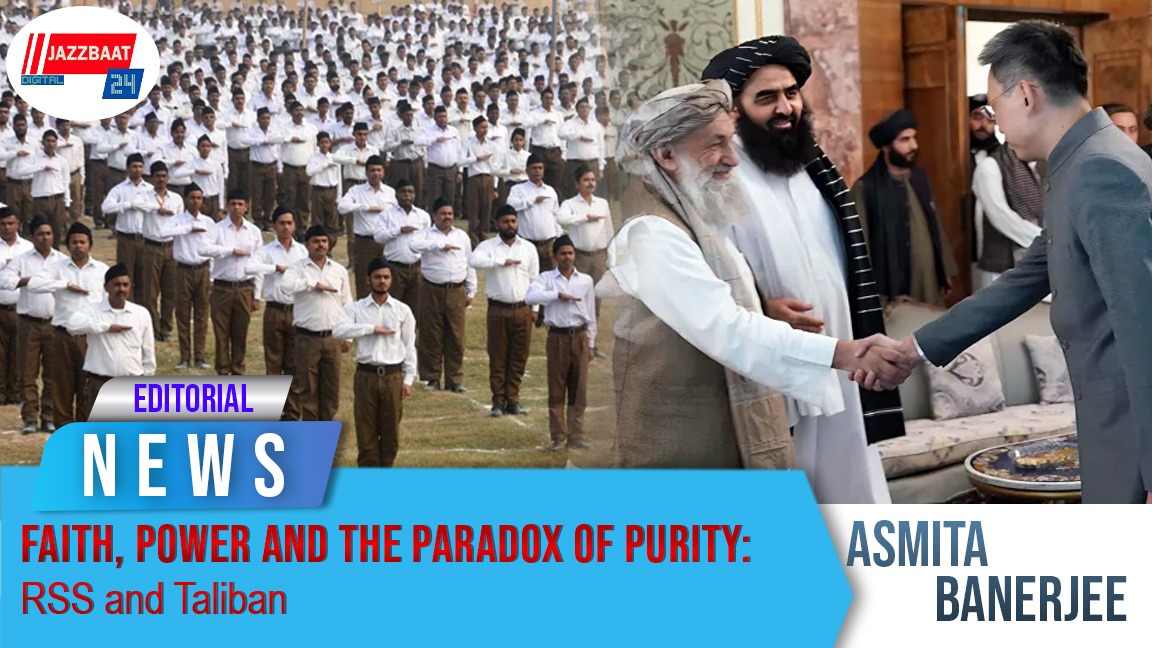

The claim that the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Taliban represent two sides of the same coin is not just an exercise in provocation. It is an attempt to hold a mirror to how ideology, when fused with religious exceptionalism, can begin to shape society in similar, unsettling ways. Both draw moral authority from faith, both seek to purify the culture around them, and both claim to protect tradition from decay. Yet, in doing so, each risks corrupting the very spiritual values it sets out to defend.

At its core, the comparison emerges from their attitudes toward diversity and dissent. In Afghanistan, the Taliban has flattened all differences to preserve its idea of Islamic order. In India, an increasingly assertive majoritarian sentiment, inspired by the idea of a “Hindu Rashtra,” has questioned the liberal spirit of equality that anchors the Constitution. Both contexts reveal an impulse to impose uniformity under the banner of cultural survival. Where the Taliban enforces it through edicts and punishments, the Indian variant manifests through cultural policing and social intimidation.

Equally revealing is the shared anxiety about gender. The Taliban’s cruel erasure of women from public life may be extreme, but the romanticisation of women’s subservience, evident in parts of Hindutva discourse, follows the same patriarchal logic. In both systems, the ideological ideal of the woman is devotional, self-sacrificing and stripped of political agency. The rhetoric differs, the principle does not.

Despite these parallels, the contexts cannot be conflated. India remains a democracy with institutional checks, vibrant dissent, and legal recourse. The RSS, however polarising, operates within the framework of civil life; the Taliban wields theocracy as the state itself. To equate the two would erase the space for democratic struggle still available in India. But to ignore their echoes would be to overlook how democracies decay not in explosions, but in quiet erosion, through the normalization of intolerance dressed as cultural pride.

The question then is not whether the two movements are the same, but whether the hunger for religious centrality, wherever it appears, nurtures the same danger: the substitution of reason with reverence and liberty with obedience. In that sense, the comparison is less about ideology and more about warning. When faith is weaponised to dictate identity or morality, the space for freedom shrinks. That lesson belongs as much to Afghanistan as it does to India.