By Dipanjan Mondal

25 June, 2025:

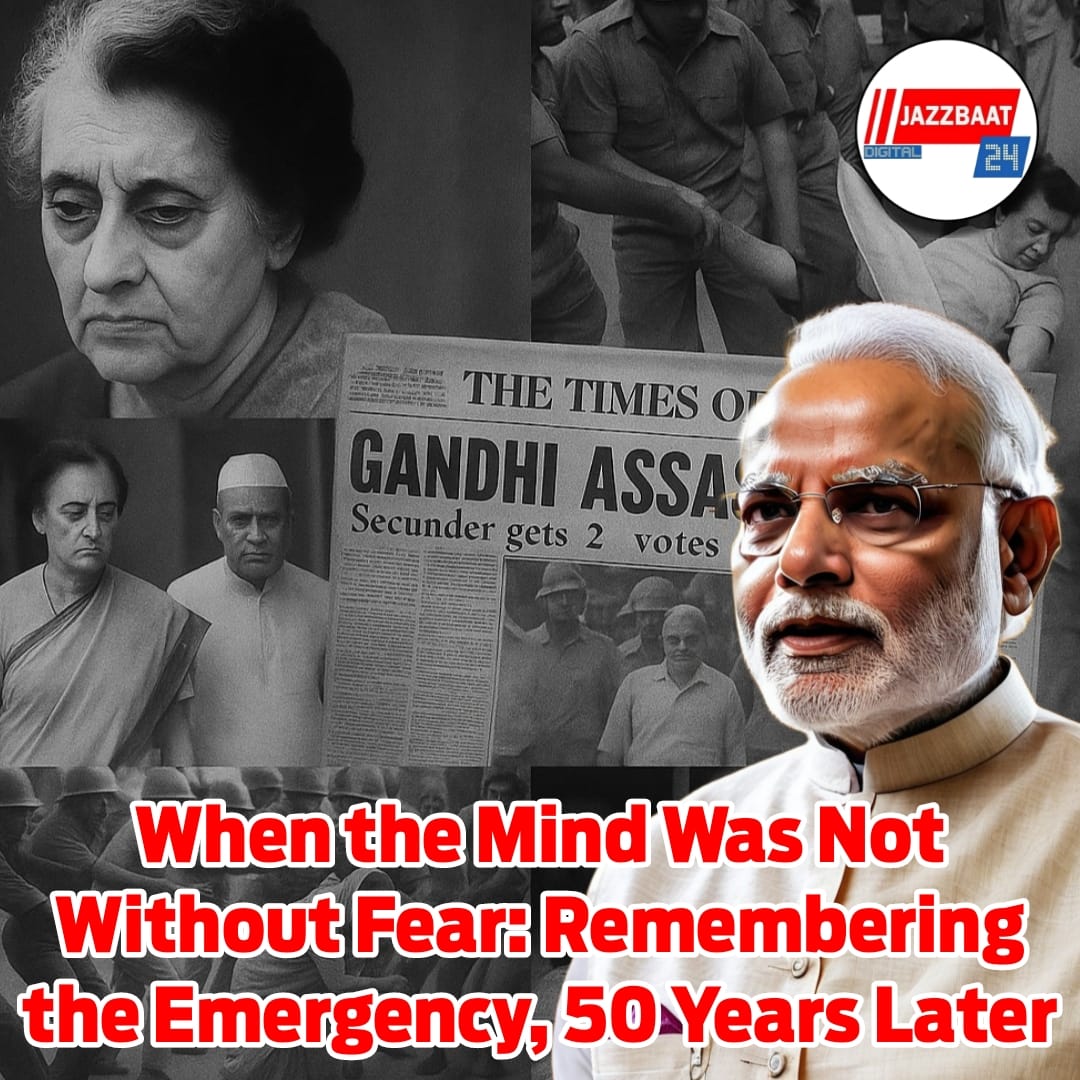

On the evening of June 25, 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's calm but solemn voice echoed over All India Radio, "The President has proclaimed Emergency..." It was promoted as a constitutional protection against "internal disturbances." However, what came next was the methodical destruction of press freedom, political opposition, and civil liberties—an authoritarian phase in India's democratic history that continues to have a lasting impact even after fifty years.

Many claim that the Emergency's seeds were planted years before it was formally announced. Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri's untimely death in Tashkent in 1966 left a leadership void in the country. The selection of Indira Gandhi as the next prime minister was not made unanimously or without opposition.

Deep rifts within the party were soon revealed when a power struggle broke out between Indira Gandhi and prominent Congress leader Morarji Desai. Gandhi gradually strengthened her position of authority by excluding critics and cultivating her own following of supporters. In 1969, the Congress formally split as a result of the division, with Indira leading a populist faction.

When Indira Gandhi was found guilty of electoral malpractices during the 1971 Lok Sabha elections by the Allahabad High Court in June 1975, the situation reached a breaking point. Her election to Parliament was deemed "null and void" by the court, which also barred her from serving for six years. Protests broke out across the country, particularly led by Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), who demanded a "Total Revolution" and her resignation.

What followed was a 21-month period (June 25, 1975 – March 21, 1977) during which India’s democratic framework was deeply tested.

Police vans had already arrived in the early hours of June 26 before the majority of the nation had woken up to the news. By dawn, more than 600 opposition leaders, including JP Narayan, L.K. Advani, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Morarji Desai, had been taken into custody. The harsh Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), which permitted detention without trial, was used to carry out the arrests.

Notably, Sanjay Gandhi, Indira's younger son, who had no constitutional position but swiftly rose to become the de facto power centre, oversaw many of these operations instead of the cabinet. The police force of Haryana Chief Minister Bansi Lal conducted violent raids in Delhi, targeting not only politicians but also journalists, activists, and even regular people who had voiced disapproval of the government.

It became evident by the morning of June 26 that censorship had been put in place. The suppression of the free press was arguably the most terrifying effect of the Emergency. Major Delhi newspaper offices lost power within hours of the announcement. When the presses stopped in the middle of printing, journalists realized something was amiss, according to Kuldip Nayar, who was editor of The Statesman at the time.

Prior to printing, all publications were now required to submit content to censors. The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting called a number of editors directly. A few newspapers made an effort to oppose; The Statesman published Rabindranath Tagore's poem "Where the mind is without fear" in protest, while The Indian Express famously left its editorial column blank one day.

But there was a price for resistance. Newspapers were closed, journalists were imprisoned, and government-critical publications were denied access to printing facilities or ad revenue. Because they did not follow the official line, editors such as B.G. Verghese of The Hindustan Times were fired. Kuldip Nayar and other individuals were detained under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA).

In order to protect press freedom, the Press Council of India was given no authority. Historian Ramachandra Guha claims that "the Emergency was an assault on the very idea of truth; it was not just the silencing of the opposition."

In addition to journalism, the Emergency resulted in forced sterilization campaigns, slum demolitions, election suspension, and the incarceration of more than 100,000 people without charge or trial. The PM's younger son, Sanjay Gandhi, who had great influence despite not having an official position, promoted many of these policies.

The Emergency was finally lifted in March 1977, when Indira Gandhi, confident of her popularity, called for elections. But the verdict was brutal. The Congress was routed. The Janata Party came to power, and for the first time, India had a non-Congress central government. The public had spoken, democracy could be wounded, but not destroyed.

Even though the effects of the Emergency are still felt, they have also been a stark reminder of what India must never again become. In addition to being the only instance in Indian history where fundamental rights were so severely restricted, it was also the only occasion when the populace peacefully rebelled and regained their right to vote.

Today, even as challenges to press freedom and institutional independence persist, the very act of remembering the Emergency keeps the democratic conscience alive. Journalists, civil society voices, and everyday citizens continue to stand up—for truth, transparency, and the right to dissent.

On this 50th anniversary, it is not just a moment to mourn the past, but to celebrate the resilience of Indian democracy, which, time and again, has shown its ability to correct course. he Emergency was a dark phase—but it is also a story of awakening AND that story continues, every time truth is spoken to power.