High in the misty hills of northeast India lies Longwa, a village where geography refuses to obey politics. Here, the India–Myanmar border is not a distant line on a map but a quiet presence running through kitchens, schools, churches and homes. For generations, the people of Longwa have lived with an unusual truth: they belong to two nations at once.

Longwa sits atop a hill in Nagaland, surrounded by forests and winding dirt roads. The most prominent building is the house of the Angh, the hereditary tribal chief of the Konyak Naga community. What makes this house extraordinary is not its tin roof or wooden beams, but the invisible line slicing straight through it. One part of the house is in India, the other in Myanmar. The Angh, Tonyei Phawang, often says with a smile, “I eat in Myanmar and sleep in India.”

For the Konyak people, borders were never meant to divide. Long before modern nation-states existed, their ancestral land stretched freely across these hills. Daily life still reflects that shared past. Villagers cross back and forth to shop, attend school, seek medical care or visit relatives. On market days, Longwa buzzes with activity as people from the Myanmar side arrive on motorbikes, balancing sacks of salt, flour, biscuits, clothes and tea. The nearest major market across the border is a day’s journey away, making Longwa a lifeline.

Until recently, this movement was legal under the Free Movement Regime, which allowed people living along the border to travel freely within a limited distance. That changed in early 2024, when the Indian government revoked the policy, citing security concerns. Plans were also announced to fence the entire 1,643-kilometer India–Myanmar border.

For Longwa, the implications are profound. If the fence follows the official boundary, it would cut through the heart of the village. Of nearly a thousand buildings, around 170 lie directly on the border line, including a school, a church and even an army camp. A fence here would not just divide land, it would split families, disrupt education and sever centuries-old traditions.

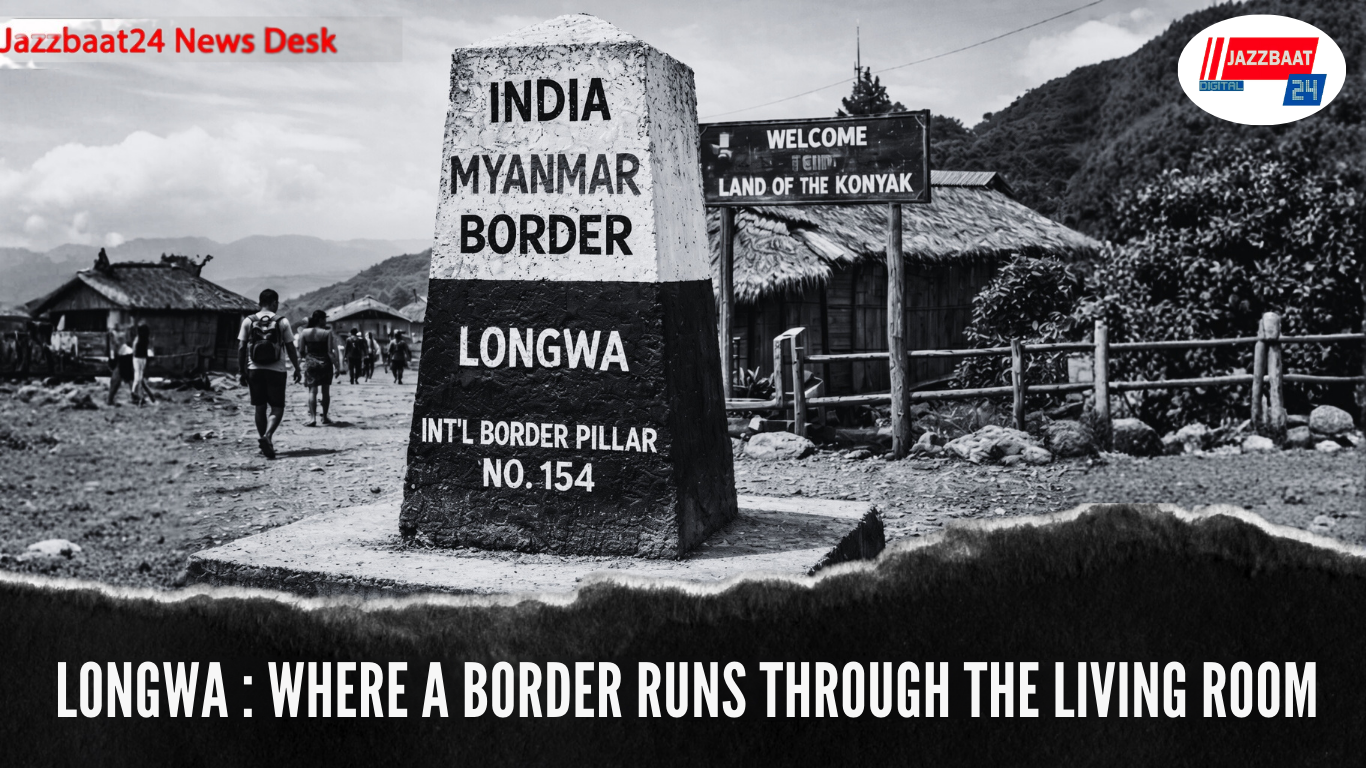

Travelers who reach Longwa often describe it as surreal. You can stand in one spot and step from one country into another without realizing it. There are no checkpoints in the village center, only a concrete pillar on a hilltop marking the international boundary. For locals, that pillar has never defined who they are. Many residents hold documents from both countries, and some even vote in elections on both sides.

The concern now is not just about inconvenience, but about survival. Students from Myanmar attend schools in India. Patients rely on clinics across the border. Farmers, traders and families depend on free movement. A rigid border threatens to turn simple daily journeys into acts of illegality.

The Nagaland state government has opposed the fencing plan, and villagers have staged peaceful protests, holding placards that read, “Respect Indigenous rights, not colonial legacy.” Community leaders argue that the border itself is a colonial artifact, drawn without regard for the people who lived there.

For travelers, Longwa is more than a destination, it is a lesson. It challenges the idea that borders are fixed and identities singular. It shows how culture, kinship and history can quietly ignore political lines. As debates over security and sovereignty continue, Longwa stands as a rare place where two countries meet not in conflict, but in shared life.

In a world increasingly defined by walls and fences, this hilltop village reminds us that some journeys are not about crossing borders, but about understanding what lies beyond them.